By Eric F. Mease

December 21, 2023

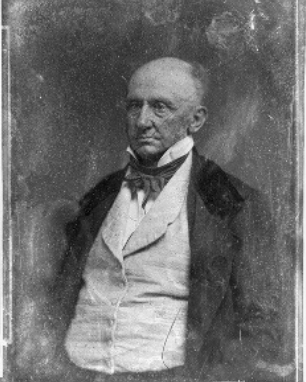

Last summer, a descendant of Col George Edward Mitchell, Henry Mustard, contributed a portrait of Col Mitchell to the Historical Society of Cecil County. Mitchell was a native of Cecil County and a hero of the War of 1812. Cecil County is no stranger to the War of 1812, see Historic Elk Landing (historicelklanding.org), where a skirmish occurred between British troops in both 1813 and 1814 involving an earthworks fort and an enslaved woman who essentially saved Elkton from the torch. But Col Mitchell didn’t fight in Elkton. He was mustered into the Regular US Army as a Major on May first of 1812, joining the 3rd Maryland Artillery Unit out of Baltimore. Mitchell himself raised a company of soldiers and headed to upstate New York where a plan to invade Canada was underway. [1]

But, I’m getting a little ahead of myself. Thirty-one years earlier, George Edward Mitchell was “probably” born in 1781, in Cecil County, at the Elkton home of Dr. Abraham and Mary Mitchell, his parents.[2] According to a biography in the Vertical Files of the Historical Society[3], the younger Mitchell studied medicine with his father, then went off to medical school at the Pennsylvania University in Philadelphia where he graduated in 1805. Mitchell attended the University when Dr. Benjamin Rush, signer of the Declaration of Independence and graduate of Cecil County’s West Nottingham Academy, was still lecturing at the University.[4] In addition, in 1802, a group of Elkton “Gentlemen,” including George Mitchell, gathered in Elkton to celebrate America’s Independence Day. Among the toasts was one from Mitchell, to “Doctor Benjamin Rush, the American Aesculapius.”[5] Soon after graduating, Mitchell was licensed to practice medicine in Maryland on June 5th, 1805.[6] Mitchell began his practice in Baltimore with “a distinguished Physician there.”[7] Just a few years later, George felt the call of politics and was elected to the Maryland House of Delegates in 1808. He was an unabashed supporter of President Thomas Jefferson who would leave office in March of 1809. In November of that year, Mitchell was elected to Maryland’s Governor’s Executive Council. He served in that position until the outbreak of the war.[8]

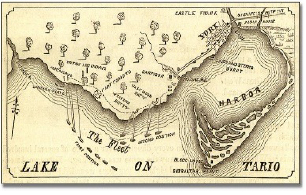

Following his enlistment in May of 1812, Major Mitchell took his company to Albany, New York, but by the winter, he was stationed at Sackett’s Harbor, New York on Lake Ontario. It was here that Mitchell was promoted to Lt. Colonel.[9] In his commission letter, President James Madison wrote, “Know Ye, that reposing special Trust and Confidence in the Patriotism, Valour, Fidelity and Abilities of George E. Mitchell I have nominated…him Lieutenant Colonel of the Corps of Artillery in the service of the United States….”[10]

According to the American Battlefield Trust website,[11] Sackett’s Harbor was both a naval and army base for the proposed invasion of Canada. That invasion began on April 27th, 1813 when American forces landed west of a fort at York, Ontario, Canada. The army was under the command of General Zebulon Pike and the undermanned fort fell fairly easily to the superior American forces. However, as the British withdrew, they set fire to their supplies. The fire spread to a powder magazine containing 500 barrels of gunpowder. It exploded killing over 200 Americans including General Pike.[12] Among the injured was Lt. Col. Mitchell, but he managed to hear General Pike’s dying orders for his second in command and Mitchell communicated those orders to General Pierce.[13]

After the explosion, “vengeful Americans ransacked the town of York, burning public buildings and businesses. This aggressive act would later be repaid when the British burned Washington D.C. in 1814.”[14]

Mitchell would participate in the capture of Forts George and Niagara and was put in command of the latter during the summer of 1813. He stayed there until February of 1814 when he and 1000 men were ordered to leave and return to Sackett’s Harbor.[15]

In the spring, Col Mitchell proceeded to a fort outside of Oswego, New York to defend American ships under construction there. According to reports, he and his 290 men marched 50 miles per day to reach the fort before the British.[16] The British fleet had one thousand troops. They began bombarding the fort on May 5th, leaving Col Mitchell and his men to scramble in their defense.[17] A major part of that defense was a diversion.

Mitchell wrote, “Not knowing on which side of the river the enemy might land, and not having enough men to defend both sides, I thought proper to deceive him and ordered the tents pitched on the village side of the river and concealed all of my forces in the fort on this side…I think it possible this artifice had the effect of making the enemy believe our force was with our tents when we had not a man or a gun on that side of the river.”[18]

Somehow, Mitchell and his men managed to repulse the first British assault. Fortunately, a storm delayed a second, giving Mitchell, “time to move vast amounts of naval supplies and stores out of reach of the British. Hopelessly outnumbered and outgunned, Mitchell’s force of 290 soldiers and sailors with 5 small cannons, endured heavy artillery bombardments and fought until driven from the fort.”[19]

Mitchell was promoted to breveted Colonel on August 14, 1815 for his actions at Fort Oswego.

The Maryland General Assembly awarded Colonel Mitchell “an elegant sword, suitable to officers of their rank, with such devices and emblems, as he may think adapted to the occasion.”[20]

Colonel Mitchell continued his military service in the Great Lakes region until the end of the war. He tried to resign from the army, but was instead “placed in command of the fourth military department” which he held until 1821 when he resigned his commission.[21]

Five years prior to his retirement, Mitchell married Mary Hooper on May 28, 1816. Following his military service, he returned to his home in Fair Hill and started a family. Together, Mary and George had 7 surviving children. Their son, Henry Hooper Mitchell, followed his father’s example by going into medicine in Elkton. He was also a Clerk of the Circuit Court of Cecil County between 1851 and 1857.[22] Arthur Whiteley Mitchell is listed as a druggist on several mid-century census. He too served a time as a court clerk from 1873 to 1879.[23] Daughter, Mary Alicia Mitchell married John Stump of Perry Point. One of their children was Judge Frederick Stump.[24] Finally, Catherine Mitchell McCullough married James McCullough and cared for her brother Henry in Elkton during his last days.[25]

Col. Mitchell For Congress!

A year after his return to Cecil County, Col. Mitchell successfully ran for the United States Congress, taking his seat in 1823. He was reelected to successive terms through 1829 when he won by 230 votes[26]. He ran for governor of Maryland unsuccessfully also in 1829.[27]

1824 was also a presidential election year when four candidates: John Quincy Adams, Andrew Jackson, Henry Clay, and Senator William Crawford ran for chief executive. While Congressman Mitchell supported Andrew Jackson, his congressional district voted for Adams. So, Mitchell vowed to support Adams when the vote for President was sent to the House of Representatives.[28]

When the US Capital was built in Washington, DC, there was a place left under the rotunda as the final resting place of President George Washington. Washington made it clear in his Will that he wanted to be buried at Mount Vernon.[29] Still, some 30 years following Washington’s death, there was discussion to bring the bodies of the President and Martha Washington to the capital. A congressional committee was formed, and Congressman Mitchell was appointed its chairman. Mrs. Washington’s grandson, George Washington Park Custis wrote a letter to Mitchell concerning his late grandmother and her husband’s eventual internment. Custis did not take a stand on the issue other than to write that “Mrs. Washington yielded to the request of Government, only in the firm and fond belief that upon her decease, her remains would be permitted to rest by the side of those of her beloved husband….”[30] Since President Washington directed that his body remain at Mount Vernon, there was no further discussion.

Aside from his war service, Congressman Mitchell is perhaps best known for his relationship with General Marquis de Lafayette. Sometime in 1823, Lafayette indicated he desired to revisit the country he had so gallantly defended during our Revolutionary War. In fact, the General had stopped at the “Head of Elk” in the spring and summer of 1781, prior to the Battle of Yorktown. Ironically, Lafayette was in Elkton the very month, March of 1781, that George was born in Elkton! The question is, did Lafayette visit George’s father, Dr. Abraham Mitchell, at the Mitchell House on Main Street in Elkton? Neither Lafayette nor his commanding officer, General Washington, mention Dr. Mitchell in their correspondence during Lafayette’s time in Elkton.[31] In his book, History of Cecil County, Maryland, George Johnston uses pages 495 to 507 to describe the accomplishments of the various members of the Mitchell family in the County. He does not mention a visit by General Lafayette to either of the Mitchell homes either in 1781, when Lafayette was in Elkton on his way to the Battle of Yorktown, or in 1824-25, when Lafayette toured the United States for the last time.[32] More on that tour later. In addition, in her book, Cecil County Maryland, A Study In Local History, Alice E. Miller devoted a page to the Mitchell family, but likewise does not mention a Lafayette visit to a Mitchell home at any time.[33] More research is required on this topic.

What everyone can agree on is that forty-three years later, in January of 1824, Congressman Mitchell authored a resolution formally inviting General Lafayette to visit the United States.

“…resolved by the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America in congress assembled that the President of the United States be requested to communicate to the Marquis de Lafayette the expression of those sentiments of profound respect, gratitude and affectionate attachment which are cherished towards him by the government and people of this country, and to assure him that the execution of his wish and intention to visit this country will be hailed by the people and government with patriotic pride and joy….”[34]

Later in the summer, Mitchell was asked to form a committee to welcome Lafayette to Maryland. The group was to have “a Troop of horse in your county” and to let the governor’s office know “the name of the Colonel of the Cavalry Regiment that this company belongs to….” That troop was to “attend at our division (state) line to escort the Gen’l to Elkton or the steam boat, that is to bring him to our city (Baltimore).”[35]

Lafayette arrived in the United States on August 15th, 1824 landing at Staten Island, New York, beginning a 24 state tour including Washington, DC. At that time Mitchell sponsored another resolution, “Resolved that the Honorable, the Speaker invite our distinguished guest and benefactor, General Lafayette, to a seat within the hall of this House, and that he direct the manner of his reception.” Mitchell then led the Congressional delegation that introduced the General to the House prior to his address in December, 1824.[36]

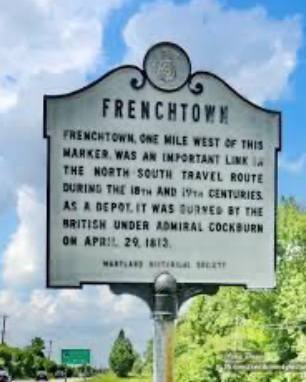

Backing up the clock a little bit, we note that, two months earlier, Lafayette also visited Cecil County in October. But, it only lasted a few hours and occurred in the middle of the night. Lafayette’s secretary, Auguste Levasseur, kept a journal during the General’s visit to the U.S. In it, he notes that Lafayette “arrived to dinner at Wilmington; this handsome town, regularly built between the Christiana and Brandywine….” “Lafayette,” Levasseur continued, “was obliged to continue his route to Frenchtown, in order to arrive the same day, where we were to find a steamboat to convey us to Baltimore.” But “we delayed for some hours in New Castle (DE), to be present at the nuptials of the son of Mr. Victor du Pont, with Miss Van dyke.”[37]

After describing the wedding, Levasseur reports that “the night was far advanced when we arrived at Frenchtown, where the steam-boat United States had waited for us a long time.”[38] Also on the steamboat was then Secretary of State, John Quincy Adams. The entourage would head off to Fort McHenry for yet another reception.[39] And therein lies the rub. Several Cecil County sources indicate that General Lafayette stopped over at Mitchell’s Fair Hill plantation for a visit during his 1824 tour. Obviously, that could not have happened. Besides, Congressman Mitchell was in Washington, DC at that time, awaiting the General for his formal visit and address to Congress.

General Lafayette Visits Cecil County a Second Time

The General would make a second brief visit to Cecil County in late July of 1825. According to the journal kept by Lafayette’s personal Secretary, Auguste Levasseur, “on quitting Lancaster (Pennsylvania), we travelled to Port Deposit, on the shore of the Susquehanna, where we were met by a deputation from Baltimore, with whom we embarked, destined for this latter city.”[40]

Following Lafayette’s return to France, he and Mitchell struck up a long-distance friendship by letter. A copy of the first letter, housed at the Historical Society of Cecil County, is dated 1826 from “La Grange,” Lafayette’s home in France. In it, the General thanks Mitchell for the warm welcome he received in Congress. “You are again by this time on the floor (of Congress) where your kind voice was heard to invite an American veteran to the most Honourable and delightful welcome that ever blessed the heart of man. The sense of that obligation to you, my dear friend, cannot but mingle with every one of the enjoyments of the recollections relative to a period of my life the happiness of which to express I could never find adequate words.”[41]

Lafayette and Col Mitchell then began a mini plant exchange. “It was reported that upon his return to France, Lafayette sent Mitchell a gift of cherry trees, to be planted on the farm at Fair Hill. Lafayette shared Mitchell’s passion for horticulture. These cherry trees are said to exist today, having been grafted years later, on what is now the Green Farm, on Route 213.”[42] It is also reported that “a paper cutter made by Henry Hooper Mitchell (George’s son) from one of these trees may be seen on display” at the Historical Society of Cecil County.[43] But the relationship did not end there. Sometime in the late winter or early spring of 1827, Congressman Mitchell reciprocated Lafayette’s gift of cherry trees with some sweet corn. In a letter dated May 29th, 1827, The Marquise thanks Mitchell for the corn which is a delicacy in France. “The several kinds of corn from Fair Hill farm, through the good care of our friend Mr. Skinner are arrived just in time to be carefully planted. It is not the first nor greatest obligation I am under to you, but I do assure you the previous invoice is very welcome….”[44]

Mitchell was back in Congress in 1830. However, while at his Fair Hill home, in October of 1831, he suffered a stroke, causing partial paralysis. Mitchell recovered enough to attend the opening of Congress in December of 1831. Upon his return to Washington, DC, letters housed at the Maryland Historical Society show he frequently updated his family on his condition. “The majority of this correspondence is from Mitchell to his sisters who were caring for his daughters and to and from his children. None of the correspondence speaks about his activities in Congress.”[45] After another attack, Mitchell died in Washington, DC on June 28th, 1831, and is buried in the Congressional Cemetery.[46]

Congressman Mitchell wrote his Last Will and Testament on February 7th of 1832. It was recorded in the Cecil County Court House on July 16, 1832. In that Will, Mitchell appointed his brother, Abraham D. Mitchell, Henry Whitely (Whiteley) of Wilmington, Delaware, and the Rev. Andrew K. Rupell of Newark, Delaware to be Executors of his Will. And he “appoint(ed) and constitute(d) them also guardians of my children during their minority. And,” he added, “my desire and advice is that said children be educated for usefuly and as far as can be under the care and superintendence of said Rupell: And that my Daughters should as much as is consistent with other arrangements for their education board with my Sisters.”[47]

He gave to his executors “for the payment of my debts and such parts of said estate as they may find necessary for that purpose.” Mitchell gave to his brother Abraham, the medical books that their father had given to George. He gave his “political books” and pistols to a Col. William Mackey as long as the pistols “shall never be lent for dueling purposes.”

George Mitchell was also an enslaver. At the opening of his Will, Mitchell addressed the future of his enslaved community. [48]

First of all, Mitchell wrote, “I leave the aged negro woman called ‘Aunt Nelly’ to the care, protection, and humanity of my brother and sisters.” There were 8 other enslaved persons listed in Mitchell’s property inventory filed in December of 1832. Here are their names and their dollar values:

1 Black Woman Elenor “Aunt Nelly” aged 68 No Value

1 Black Woman Caroline aged 27 $112

1 Black Woman Precillo aged 20 $100

1 Black Woman Nancy aged 18 $100

1 Black girl Rose aged 6 $75

1 Black Man Charles aged 24 $150

1 Black twin aged 24 $150

1 Black boy Fortune aged 14 $125

1 Black boy Simon aged 7 $100[49]

Unlike Thomas Jefferson, who could not free his enslaved persons due to crushing debt, Mitchell had the rest of his estate to pay his debts. So, he could have freed his enslaved persons as George Washington did. He choose not to. Instead, Mitchell gave his enslaved persons to one of his executors. “I give and bequeath to Col Henry Whiteley of Wilmington in the State of Delaware all my slaves that I shall have at my decease to be by him delt with and dispersed of (emphasis added) at his discretion and they are recommended (emphasis added) when he can do so consistently with the laws of the State.” Whiteley could have freed these enslaved persons too, because it was legal for him to do so in Delaware and in Maryland.

According to records in the Delaware State Archives, Whiteley did not indenture his inherited enslaved persons or sell them.

Whiteley does not appear as living or being an enslaver in Cecil County in either the 1830 or the 1840 U.S. Census.[50] The Maryland Archives contain no record of Whiteley granting any Certificates of Freedom or manumissions.[51] Whiteley died in 1841. His Property Inventory notes that he enslaved 6 individuals, however, their names do not match those he inherited from George Mitchell a decade earlier.[52]

George Mitchell’s brother, Abraham, did not note any sales of enslaved people in his account of his brother’s expenses.[53] Abraham did not take George’s enslaved persons either, as he has no enslaved persons listed on the 1840 US Census.[54] However, the Census may not tell Abraham Mitchell’s entire enslavement story. According to an advertisement in the Cecil Whig, the County Orphans Court ordered a Public Sale of Abraham’s “personal property” following his death in December of 1841. At the bottom of the advertisement it states, “P.S. Will be offered at private sale on said day 1 Negro Woman and Child, and 2 Negro Girls.”[55] [56]

So what happened to George Mitchell’s enslaved persons? While there is no official record of what Whiteley did, there is another, not so public possibility.

Professional title searcher and both frequent volunteer and researcher at the Historical Society of Cecil County, Darlene Mccall, has a theory. “I think,” Darlene writes, “that Henry quietly took the slaves to his home in Wilmington and then helped them to make the trip North. He could have given them passes to Philadelphia by boat or transported them himself to Philadelphia.”

This is a feasible theory for two reasons: First, as Darlene points out, “George (Mitchell) is not saying ‘sell them’ or manumission them, but dispose of them at his discretion.” Secondly, there is record of Whiteley freeing one and possibly 2 others of his enslaved people. One Delaware record shows that Whiteley freed an enslaved individual named Michael Murray when Murray turned 21 years of age.[57] In addition, in his Last Will and Testament, Whiteley bequeaths “to my daughter, Mary Carol, my Negro girl named Leah, whose term of service will expire at the age of 21 (emphasis added).”[58]

More research is necessary to find out what really happened, or the answer might be lost in the mist of time. However, by giving all of his enslaved persons to Whiteley, Mitchell ensured that, at least for the time being, the enslaved families, if any, would not be broken up. There were no guarantees, long term.

A sidebar, in September of 1835 the Fair Hill plantation was sold to Henry Whiteley of Delaware.[59]

Another mystery.

George Mitchell’s Property Inventory shows he owned 9 persons upon his death. However, according to the 1830 Federal Census (taken just 2 years prior to his death), George Mitchell enslaved 10 persons: one male under 10 years old, one male between 10 and 23 years old, 3 males between 24 and 35, one female under 10, 2 females between 10 and 23, one female between 24 and 35, and one female between 36 and 54. The inventory is missing a black male between 24 and 35. As noted, the “one female between 36 and 54” is probably the “Aunt Nelly” singled out by Mitchell for “the care, protection, and humanity of my brother and sisters.” Another mystery for future researchers to solve.

In 1826, George Mitchell was running for his third term in Congress when a farmer from Harford County wrote a letter describing the Congressman: “In Congress, he was a judicious friend of the Manufacturing and Agricultural interests and of internal improvements. Each session, he was a member of one of the most important standing committees. His vigilance for our welfare has illuminated and adorned our majestic river and spacious bay with elegant lighthouses.”[60] Not a bad legacy for George Edward Mitchell: husband, father, farmer, doctor, war hero, Congressman, friend, and son of Cecil County.

##

[1] From the Vertical Files of the Historical Society of Cecil County, MD; Yellow legal sheets and a lengthy family bio by Mary M.M. Hansen of Perryville, MD in June of 1939, some of which is taken from Johnston’s History of Cecil County, MD p 495; published in 1881.

[2] National Register of Historic Places Inventory Nomination Form, United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service, Date entered May 13, 1976, page 2 of the Significance segment of the Inventory form, page 6 overall.

[3] Ibid

[4] National Library of Medicine, National Center for Biotechnology Information, “Benjamine Rush, MD: assassin or beloved healer?” by Robert L. North, MD, January, 2000, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1312212/

[5] Aurora General Advertiser, Philadelphia, Monday, July 12, 1802

[6] From the Vertical Files of the Historical Society of Cecil County, MD; Yellow legal sheets and a lengthy family bio by Mary M.M. Hansen of Perryville, MD in June of 1939, some of which is taken from Johnston’s History of Cecil County, MD p 495; published in 1881.

[7] Obituary of Col. George E. Mitchell published in the U.S. Gazette for the Daily Chronicle of Philadelphia, July 7, 1832

[8] Ibid

[9] “The Mitchell House Fair Hill, Maryland”, Bulletin of the Historical Society of Cecil County, from “Talk to Historical Society of Cecil County”, January 18, 1975. No page number on the page.

[10] George Edward Michell’s Commission in Army as Lieutenant Colonel, March 3, 1813 as found in the Mitchell folder of the Vertical Files in the Historical Society of Cecil County.

[11] American Battlefield Trust web site, https://www.battlefields.org/learn/war-1812/battles/york posted in 2003

[12] Ibid

[13] From the Vertical Files of the Historical Society of Cecil County, MD; Yellow legal sheets and a lengthy family bio by Mary M.M. Hansen of Perryville, MD in June of 1939, some of which is taken from Johnston’s History of Cecil County, MD p 495; published in 1881.

[14] American Battlefield Trust web site, https://www.battlefields.org/learn/war-1812/battles/york posted in 2003

[15] From the Vertical Files of the Historical Society of Cecil County, MD; Yellow legal sheets and a lengthy family bio by Mary M.M. Hansen of Perryville, MD in June of 1939, some of which is taken from Johnston’s History of Cecil County, MD p 495; published in 1881.

[16] Ibid

[17] Ibid

[18] “The Mitchell House Fair Hill, Maryland”, Bulletin of the Historical Society of Cecil County, from “Talk to Historical Society of Cecil County”, January 18, 1975. No page number on the page.

[19] The Battle of Oswego, WCNY, PBS, by Paul Lear, Historic Site Manager, Fort Ontario State Historic Site. https://www.wcny.org/education/war-of-1812/the-battle-of-oswego/

[20] Resolution of the General Assembly of Maryland, Annapolis, January 10th, 1816

[21] “The Mitchell House Fair Hill, Maryland”, Bulletin of the Historical Society of Cecil County, from “Talk to Historical Society of Cecil County”, January 18, 1975. No page number on the page.

[22] Maryland Manual On-Line: a Guide to Maryland and its Government. https://msa.maryland.gov/msa/mdmanual/36loc/ce/jud/clerks/former/html/00list.html

[24] “The Mitchell House Fair Hill, Maryland”, Bulletin of the Historical Society of Cecil County, from “Talk to Historical Society of Cecil County”, January 18, 1975. No page number on the page.

[25] Obituary of Catharine W. Mc Cullough, The Cecil Whig, page 1, December 23, 1899.

[26] The Delaware Register, or Farmers’, Manufacturers’ and Mechanics’ Advocate; Saturday, October 10, 1829, p. 6

[27] From the Vertical Files of the Historical Society of Cecil County, MD; Yellow legal sheets and a lengthy family bio by Mary M.M. Hansen of Perryville, MD in June of 1939, some of which is taken from Johnston’s History of Cecil County, MD p 495; published in 1881.

[28] Ibid

[29] George Washington’s Last Will and Testament, July 9, 1799, from the George Washington’s Mount Vernon web site: https://www.mountvernon.org/education/primary-source-collections/primary-source-collections/article/george-washingtons-last-will-and-testament-july-9-1799/#:~:text=To%20my%20dearly%20beloved%20wife,Pitt%20%26%20Cameron%20streets%2C%20I%20give

[30] Letter from George Washington Parke Custis to the Honorable George E. Mitchell, Esqr., Chairman of Committee, etc, etc, etc. dated Arlington House, 27th Feby., 1830.

[31] Founders Online, National Archives, Washington, DC, https://founders.archives.gov/

[32] History of Cecil County, Maryland and the Early Settlements Around the Head of Chesapeake Bay and on the Delaware River, by George Johnston, copyright 1881 and published by the author. Pages 495-507

[33] Cecil County, Maryland: A Study in Local History by Alice E. Miller, copyright 1949 by C & L Printing and Spcialty Co., Elkton, Maryland. Pp. 61-62

[34] Resolution of the Senate and House of Representative of the United States of America in congress assembled, sponsored by Congressman George E. Mitchell of Maryland, January 12, 1824.

[35] Letter from Wm. Dickinson of Baltimore, Aug. 26, 1824 to Col. George E. Mitchell, Elkton, MD, from the Mitchell folder in the Vertical Files of the Historical Society of Cecil County.

[36] From the Vertical Files of the Historical Society of Cecil County, MD; Yellow legal sheets and a lengthy family bio by Mary M.M. Hansen of Perryville, MD in June of 1939, some of which is taken from Johnston’s History of Cecil County, MD p 495; published in 1881.

[37] Lafayette in America in 1824 and 1825; Journal of a Voyage to the United States, written by Auguste Levasseur, translated by Allan R. Hoffman, published in France in 1829, p 160.

[38] Ibid

[39] Ibid

[40] Ibid, p 240

[41] Type written transcript of a Letter, Marquise de Lafayette to George Mitchell, from La Grange, dated 1826, no month listed. Mitchell folder in the Vertical File, Historical Society of Cecil County, Maryland.

[42] Standing at the Crossroads in Cecil County, Maryland: The Making and Re-making of a Colonial Tavern, The Mitchell House at Fair Hill. By Tracy Hill Jentzsch Master’s Thesis, University of Delaware, Spring, 2014, p. 80

[43] “The Mitchell House Fair Hill, Maryland”, Bulletin of the Historical Society of Cecil County, from “Talk to Historical Society of Cecil County”, January 18, 1975. No page number on the page. Picture curtesy of the Historical Society of Cecil County, MD

[44] Letter from Lafayette to George E. Mitchell, M.C., May 29th, 1827 from the Mitchell folder in the Vertical Files of the Historical Society of Cecil County, Maryland.

[45] Series IV: Maxwell Family Papers, Dates: 1806-1881, Maryland Historical Society, https://mdhistory.libraryhost.com/repositories/2/archival_objects/163842

[46] Biographical Directory of the United States Congress, 1774-2005; George Edward Mitchell as posted in Ancestry.com Biographical Directory of the United States Congress, 1774-2005 – Ancestry.com

[47] Last Will and Testament of George E. Mitchell, written on February 7th, 1832 and recorded on July 16, 1832. Some of the word spellings are as Mitchell wrote them.

[48] There were 1705 enslaved individuals living in Cecil County in 1830 according to the Maryland State Archives Legacy of Slavery in Maryland project website. The census data was accessed from the University of Virginia Historical Census Browser. http://slavery.msa.maryland.gov/html/research/census1830.html

[49] The Property Inventory of the George Edward Mitchell Estate filed with the Cecil County Register of Wills on December 11th, 1832 as found on the Maryland State Archives web site: https://pve.msa.maryland.gov/pages/viewer.aspx?VLUkh24OB8RnE8v1iqw1Q7JDCSe+LtodPbj+VMtoJamo9XDfbFBIbAPpt9RguGvx9j5Y1xc6A8KET%2fpAQK53Kw=%3d

[50] United States Census, 1830 and 1840 as posted on Ancestry.com

[51] The Maryland State Archives Legacy of Slavery in Maryland web site: https://slavery2.msa.maryland.gov/pages/Search.aspx

[52] Property Inventory of Henry Whiteley, Filed Register of Wills, New Castle County, DE, January 5, 1842.

[53] Accounts of George E. Mitchell, filed in the Register of Wills, Cecil County, MD, May 22, 1842 by Abraham D. Mitchell.

[54] 1840 United States Federal Census for Abram D. Mitchell, District 2, Cecil Maryland from Ancestry.com https://www.ancestry.com/discoveryui-content/view/1378447:8057?tid=&pid=&queryId=bd72eb20-daf9-485b-98c1-1fd2357489aa&_phsrc=luo1294&_phstart=successSource Abraham Mitchell does own 5 enslaved persons, as listed in the 1830 Federal Census as retrieved from Ancestry.com

[55] Public Sale notice from the Cecil Whig, Saturday, February 26th, 1842

[56] This advertisement shows, not only the public sale of human beings in Cecil County, but the possibility that an enslaved mother and her child may be separated in that sale.

[57] Manumission of Michael Murray, Recorder of Deeds, New Castle County, DE, June 8, 1841, as posted in Ancestry.com

[58] The Last Will and Testament of Henry Whiteley, filed October 7th, 1841 in the New Castle, Delaware County Court House, page 1

[59] Deed JS 35-404, September 14th, 1835, Recorder of Deeds, Cecil County Court House.

[60] “The Mitchell House Fair Hill, Maryland”, Bulletin of the Historical Society of Cecil County, from “Talk to Historical Society of Cecil County”, January 18, 1975. No page number on the page.

Col George Edward Mitchell

Home of Dr. Abraham and Mary Mitchell

Historic map of Ontario Canada

Defending American ships

Col. Mitchell

Frenchtown marker