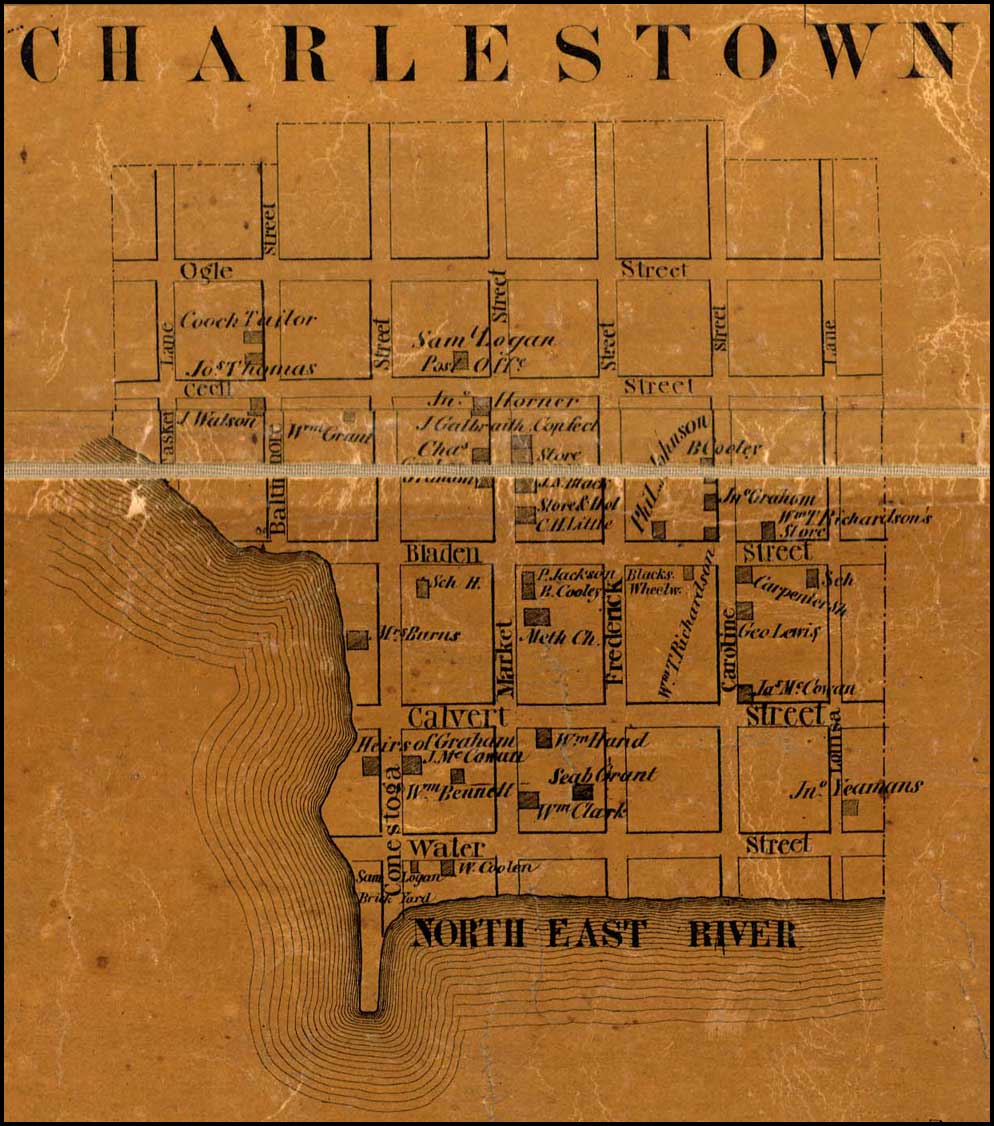

Charlestown, Maryland

Constructed 1742 – 1789

Listed on the registry – April 14, 1975

Significance: (From mht.maryland.gov)

The Charlestown Historic District is a significant part of Maryland’s past. Although the streets are now paved, the town is basically the same today as it was when it was the major shipping center of the head of the Chesapeake Bay. The original town records, minute books, and ledgers of the Town Commission are still extant. In selecting a location that was strategically located at the head of the Bay, the 1742 Maryland General Assembly enacted a law “for laying out and erecting a town at a place called Long Point on the west side of North East River in Cecil County.” In the same enactment, the name of Charles Town was established for the new town and shipping center. Charlestown was the county seat from 1782 to 1787 and, while no courthouse was ever built, there was a small stone jail. While its plan was inspired by Philadelphia, its architecture witnesses its location in Tidewater Maryland, undoubtedly the result of its economic orientation to the Chesapeake Bay waters. Only in areas of Cecil County away from the water are the earliest buildings closely related to those of adjacent Pennsylvania. Charlestown was a town of a prosperous working class, serving the surrounding countryside. The water was its network of transportation, closely linking it economically with all the towns of the Chesapeake Bay country. By the turn of the 19th century, Elkton had eclipsed Charlestown as the urban center of Cecil County. The financial decline worked as a freezing agent to retain Charlestown’s 18th century character, and many of its original buildings.

About the Property (from mht.maryland.gov)

Charlestown Historic District comprises a 150-acre portion of the town of Charlestown. All known existing 18th century features of the town are included within this district, which is bounded by Tasker Street, Ogle Street, Louisa Lane, and the North East River. Charlestown has been passed by the more devastating aspects of progress–highways and urbanization. Thus its original size is, basically, its present size; its overall density, probably, has never changed; its original plan, based on the Philadelphia street plan, survives, virtually unaltered; and a high percentage of its earliest buildings still stand, many with only few alterations. There are approximately 150 buildings in the district. Although there are several good examples of the Victorian era, many structures that appear to be of late-19th and early-20th century construction are in reality of a much earlier time. Because of the poor economy of the town during the first part of the 20th century, very few new homes were built, the usual Charlestown practice being to alter or add to an existing structure. It is believed that many 18th century structures are yet to be identified. At present there are 14 houses known to have been constructed during that century. Charlestown had no great mansions. Its largest structures were the inns and hotels which served the popular Charlestown Fair in the colonial period. Among the smaller buildings, a symmetrical three bay scheme, with the door centered, occurs with noticeable frequency. Some are 1 1/2 stories in height, others are two. In the latter, the central bay of the second story is usually without an opening. The first stories of these houses may have one or two rooms, but they have no passage; stairs usually ascend in winders beside the chimney breast. Chimneys are almost always internal and fireplaces are large, expected characteristics for this northern Maryland town. Several gambrel roofs survive in Charlestown, indicating the popularity of that roof form in the 18th and early 19th century. Such a roof could be framed with relatively short members, allowing a maximum useable floor space in the upper story, not possible with a gable roof of any practicable pitch. Several early buildings are of log construction, a very respectable building material by the mid to late 18th century, for they are finished as sophisticated small houses, even with paneled walls. Stone was also a readily available material, unlike many areas of the Bay country to the south. Stone construction should not be considered as influenced by Pennsylvania, but simply as allowed by geology. Clay was abundant, too, so Charlestown had, and has, early buildings of log, frame, stone, and brick construction–all the known 18th century materials.

For more information, visit https://www.charlestownmd.org/charlestown-history/